Last month I wrote about the importance of drawing something every day, and the effects it has on your brain. But there are times when it just… Doesn’t happen. And that’s also because of brain stuff: Especially anxiety, which can hamper the drawing process both mentally and physically.

The Wacom One is aimed at people in that awkward intermediate stage—past the luck and excitement of a beginner’s honeymoon stage, but not quite at the level of a seasoned pro who can sit down and bust it out like a machine—in other words, the people who might most understand the struggle of self-motivating. Ideas flow and dance through your mind all day, but the moment you sit down at the tablet, you forget not just what you wanted to draw, but how to use Photoshop and what pen is.

So here are the steps to getting started with a drawing session. (Drawings done on the Wacom One with Clip Studio Paint.)

Part 1: Mental

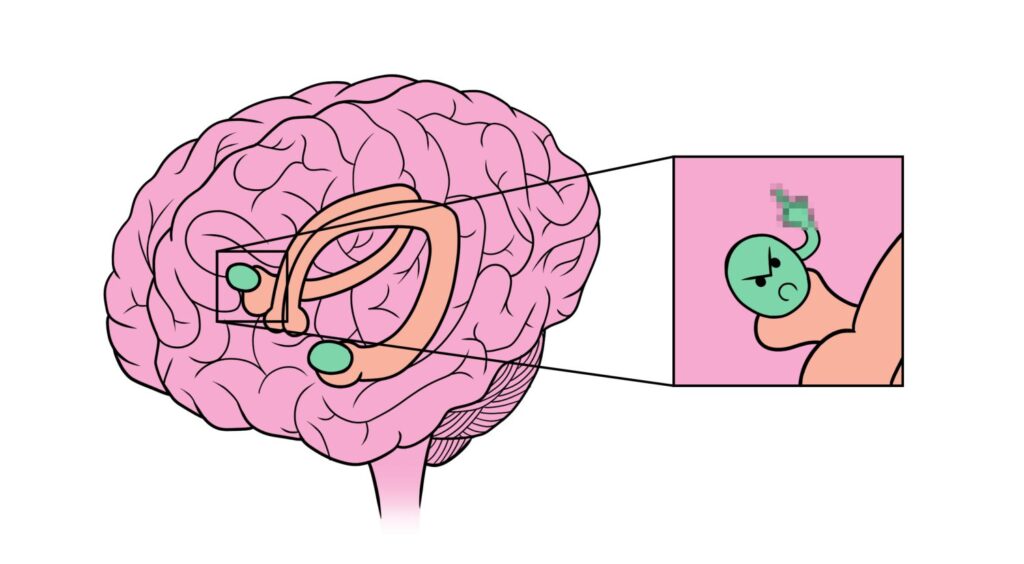

Procrastinators tend to self-deprecate by saying they’re just lazy: especially artists, who are haunted by the stereotype of laziness wherever we go. But more likely, it’s actually fear. And we know the scientific cause: Your right amygdala.

The amygdalae are two coffee-bean-sized parts of your temporal lobes that regulate your emotions. The left regulates multiple ones, where the right specializes in fear, storing and recalling triggers.

It’s been found that chronic anxiety swells the amygdalae, making them stronger and perpetuating the anxiety in a vicious cycle—over time, they can increase up to three times their size—and that people who suffer from mental difficulties that prevented them from getting to work consistently have larger ones. So if anyone asks, you can say you’re not procrastinating, it’s just big brain time.

How do you actually get to work, though?

In some cases, the solution is just sitting down and powering through it because it has to be done. But in others, it’s to relax.

If you stop and actually pay attention to how you feel when you’re imminently faced with doing a task you’ve been procrastinating on, you might notice your breathing is shallower than normal, or your body is tightly wound to the point where it can even cross the line into physical pain.

And it turns out that’s caused by your expectations. When you impose too many conditions on yourself, shame yourself for not drawing fast or well enough, or pressure yourself to not mess up a drawing, it turns your amygdala on. You might not notice this, but over time, you’re building up a subconscious aversion to drawing, making it something you associate with guilt and negativity. Your amygdala will activate your stress response whenever you have to do it, meaning you’ll need to bring yourself down before you can get any work done.

If you find you have to calm yourself down by surfing the internet or getting lost in a distraction before you’re calm enough to draw, that might be why: You’re no longer seeing it as fun, but as the chore you have to put off by doing something fun. Some of you reading this might think I’m soft-pedaling it or making excuses for laziness, but it helps no one to be that reductive.

The real solution is to do what you can to dissociate art from those feelings of unpleasantness. Practice calming down, having more realistic expectations of your drawings, and removing the pressure to make each one flawless.

If you struggle with this problem, here are three homework assignments. Do one of these next time you get to work. I promise, they’ll make things easier.

- Find an active art Discord where you can stream your drawing program. Being around friends and other users enjoying themselves will lessen the tension. And they’ll often provide positive feedback, inspiring you to keep going.

- Meditate for one minute before you start drawing.

- Put on a comedy album or podcast while you draw. (Audio only. Nothing you have to watch.) Having your drawing stress periodically interrupted by laughter will break the tension and create a positive association in your mind.

Finally, the most optimistic thing I can say is that it gets easier with practice. The more you practice buckling down, the better you’ll get at it. It doesn’t happen overnight. And the more you draw, The more confident you’ll get that you can draw a difficult subject without blowing a brain vessel, so the less stressful drawing will be.

If It’s Still Not Working, Reevaluate What’s Wrong

…Sometimes, you try everything and it still just doesn’t come. Maybe it’s not just that the act of doing it feels intimidating, but the very idea of doing it just seems miserable. You don’t even care to see the final product that much, you just want it behind you so you can do something that doesn’t suck.

If that’s the case, your failure to launch might be telling you there’s something fundamentally misconceived about the task at hand. There have been way more times than I can count when I’ve sat and been unable to do the thing for hours, then I decided to try drawing it from a different angle or with a different composition, and suddenly it just flowed out and the piece came together—or at least I could see a clearer path to the end from that point.

There are people who’ll disagree with me on this—some of them industry professionals who have way more right to talk about it than I do—but drawing isn’t as linear as moving boxes from one place to another. There’s never just one way to draw a thing, or to solve a problem you encounter when drawing it.

For some artists, it really is as simple as sitting down and drawing the subject in the way they best know how, at a steady pace until it’s done. Others work in bursts, but get a comparable amount of work done in the end. Simply learning your style and how to work with it goes a long way.

Part 2: Physical

Untense

Hand, arm, and shoulder injuries are omnipresent among artists. And once again, that dastardly anxiety’s to blame. You can actually prevent physical injury by consciously untensing before you draw.

And it’s more important than you might think. Stress has been shown to cause muscle rigidity and poor hand-eye coordination in athletes. Fewer physicians study digital artists, but we can assume the same for us. That means less fluid, less controlled drawings and a higher risk of repetitive strain injury.

This is a several-step process, beginning with when you first sit down.

Step 1: Back against the seat

And keep it there.

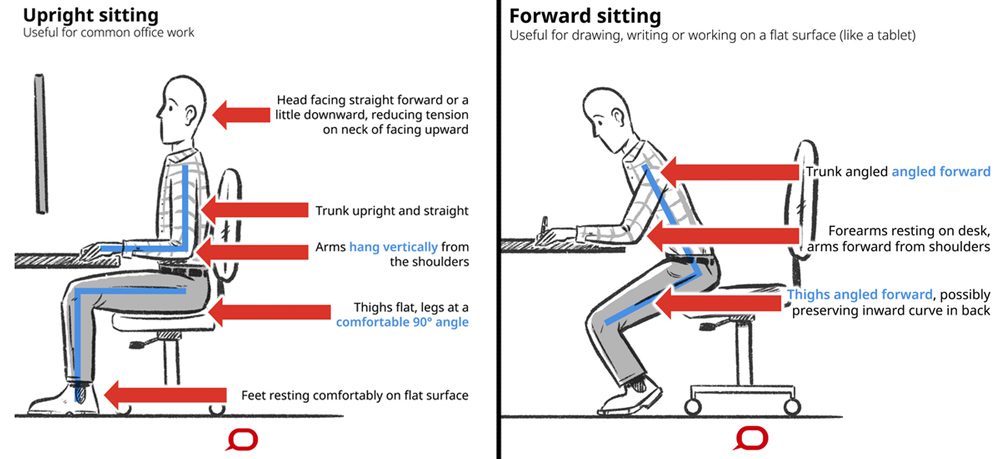

Images from Quartz at Work

Upright sitting is preferable, although the requirements aren’t as rigid as shown here. If you can avoid forward sitting, do so whenever possible. If you’re using a flat tablet or a drawing monitor set at an appropriate angle, you should only need to use it while drawing on paper. Reclining is OK, but makes using a tablet harder on your arm.

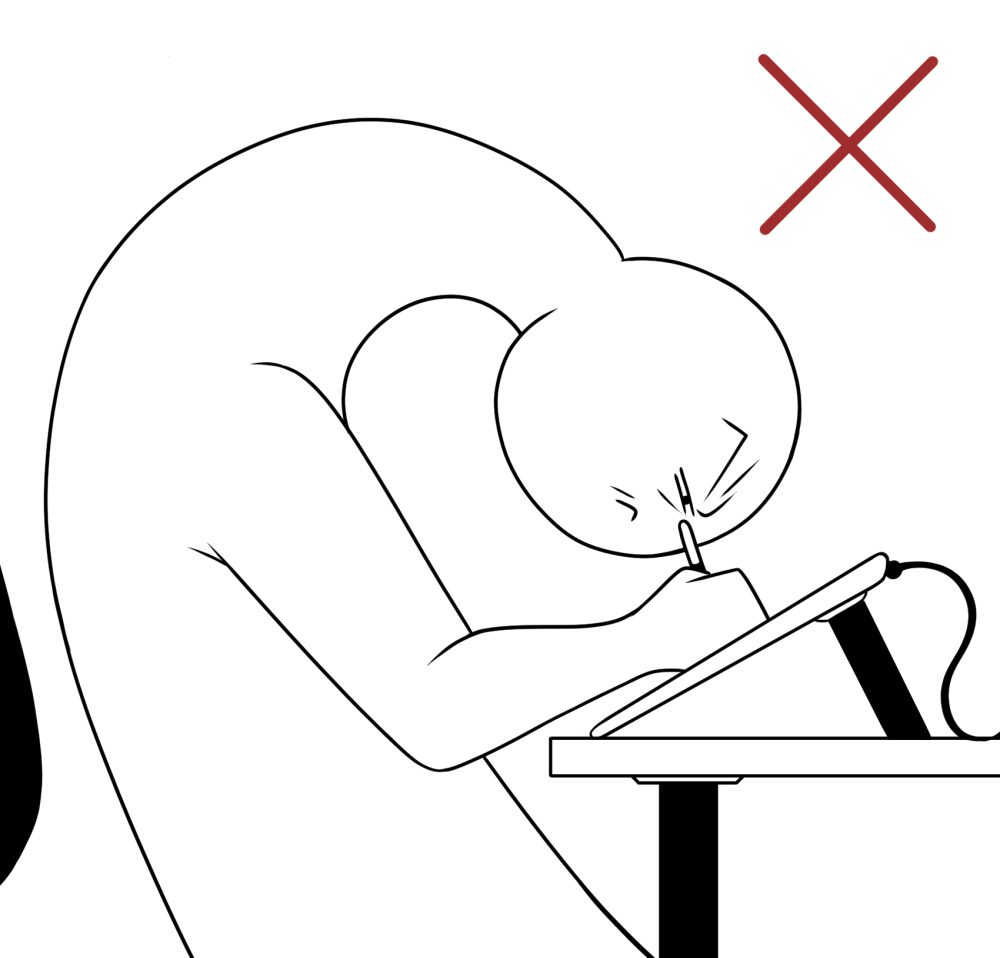

And if you must use the forward sitting position, bend at the waist as shown. Hunching with your upper back is a one-way ticket for the pain train.

Step 2: Do This Stuff

If you’re reading this release your shoulders from your ears, unclench your jaw, and remove your tongue from the roof of your mouth. We physically tend to hold onto stress in least noticeable ways. Relax.

— devyn (@sentfromdevyn) August 6, 2018

It might seem like a copout, but she explained it much better than I could.

Most stress is carried in the “tension triangle” between your forehead (hence worry lines) and your shoulders. Particularly important is the shoulders part. They carry the bulk of it and have the capacity to most affect our drawing.

“’Without even realizing it, [office workers under stress] hold their bodies in a tense, alert pose day after day,” says physical therapist and professor Steven Wolf. ”The buildup continues each day as the tensions repeat. As time goes on, their neck and shoulder muscles get shorter and shorter.”

If you notice them creeping up, lower them.

Step 3: Warm Your Hands

It might not feel like it this year, but it’s still technically winter, so keeping your hands warm is particularly important. If you have a space heater, make sure to hold your hands in front of it periodically. It keeps them limber. No matter what, make sure not to draw when they actually feel cold. Swear, it’s like having rigor mortis.

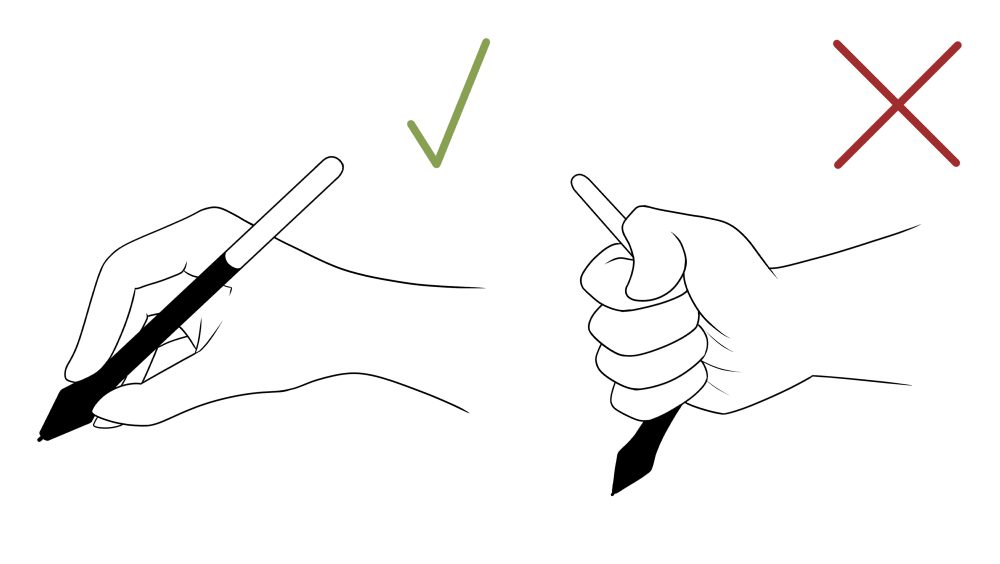

Step 4: Release Your Death Grip on the Pen

When you’re tense—say, you’re worried about a deadline or frustrated that a piece isn’t coming out how you want—that stress manifests itself in your grip tightness.

Other professions talk more about this than us. Guitarists warn against crushing the strings into the fretboard, since it limits your mobility and how quickly you can change positions. Calligraphers caution that too much pressure will ruin the stroke. It’s time we started as well. This is one of the most important things to be mindful of, since it paradoxically ruins the amount of control you have over the drawing, as well as causing you to get fatigued faster and slowly wearing out your hand.

It might scratch your screen, too.

Step 5: Exhale

Stress causes shallower, faster breaths. Simply regulating it can greatly reduce tension. Make sure to stop periodically to breathe deeply, and be mindful of your no WAIT

Sorry, that must be stressful.

As I’ve mentioned before, having a fun tool to work on lessens the anxiety of drawing, and I can attest that the One is a lot of fun. It has a great feel, making it comfortable to draw on. It’s easily portable—you can even run it off your laptop’s power, which I’ll be discussing in a future article, meaning that if you’re struggling to work at home, you can take it to a more pleasant environment. It’s also worth noting its pen is lighter and easier on the hands than the Intuos or Cintiq, though, meaning you need less pressure to draw with it.

Just saying.

About the Author

CS Jones is a Philadelphia-based freelance writer and illustrator. He’s trying to take this advice himself, as he’s a chronic procrastinator with finger pain. His work is best seen at thecsjones.com or @thecsjones on Instagram.