Header from Gorillaz Wrap 2020

2020 will mainly be remembered as the year that made us want to give 2016 a big, wet kiss. But it also looks like it’ll be the start of a decade of great change. It was the product of problems that were allowed to fester for a long time, societal issues that we’re now being forced to address. Here in the US, especially, it was a warning of how many of the systems we rely on are broken, a reckoning with old social attitudes, and a reminder that sometimes the most devalued jobs are truly the most important.

It was a year of contradictions. The pandemic brought out the best and worst in people. Protests and counterprotests showed us both solidarity and racial terrorism. It was a year of telecommuting and DoorDashing, community spirit and isolation, social justice and parasocial relationships.

It was also arguably the single most important year for digital media.

2020 changed the internet, online events, advertising, social media, and distribution platforms, and digital art with them. People were more online than ever. Artists lost cons and galleries, but gained animation commissions, design work, and even ad agency jobs—Digital Arts Online went as far as to say illustration is now more important than ever. Freelancing in the current climate is high-risk, but also potentially high-reward: Some lost their entire living, but one I talked to made over $200,000 last year making downloadable assets for online Dungeons & Dragons games.

The art world made some truly groundbreaking changes to adapt, some of which might set permanent precedents. And in the background, some other cool things happened that were unrelated to the pandemic. So, here are some of both:

Virtual events were normalized

Back when cons made all their money off ticket sales, the best you could hope for would be to find videos of individual panels on Youtube. And even then, you’d have to get your hands on the con schedule to even know to look for them. And it was unheard of for an entire major convention to be livestreamed.

…Now, of course, the pandemic’s taken us too far in the other direction, getting rid of the physical part altogether. But consider the price of this year’s online conventions versus their real-life equivalents in previous ones. Lightbox in 2019 was $135 for the weekend. Lightbox 2020 started at $1.

And that was just one of many online events and webinar series, some of which flew under the radar at their airing times but are now archived to watch and learn from at any time. There was Adobe MAX. There was Wacom’s Connected Ink, which I wrote a retrospective of. There was Comic-Con@Home, featuring the casts of Walking Dead and His Dark Materials, and many similar events that weren’t explicitly art-themed, but featured artist vendors and guest speakers.

If they take the lessons they learned during the pandemic to heart, we might see future cons become simultaneous live and digital events. Perhaps we’ll see panelists interacting with live audiences and stream viewers simultaneously, maybe even taking questions from chat. Perhaps the days of having to fly to San Diego to see a single artist speak are nearing a close.

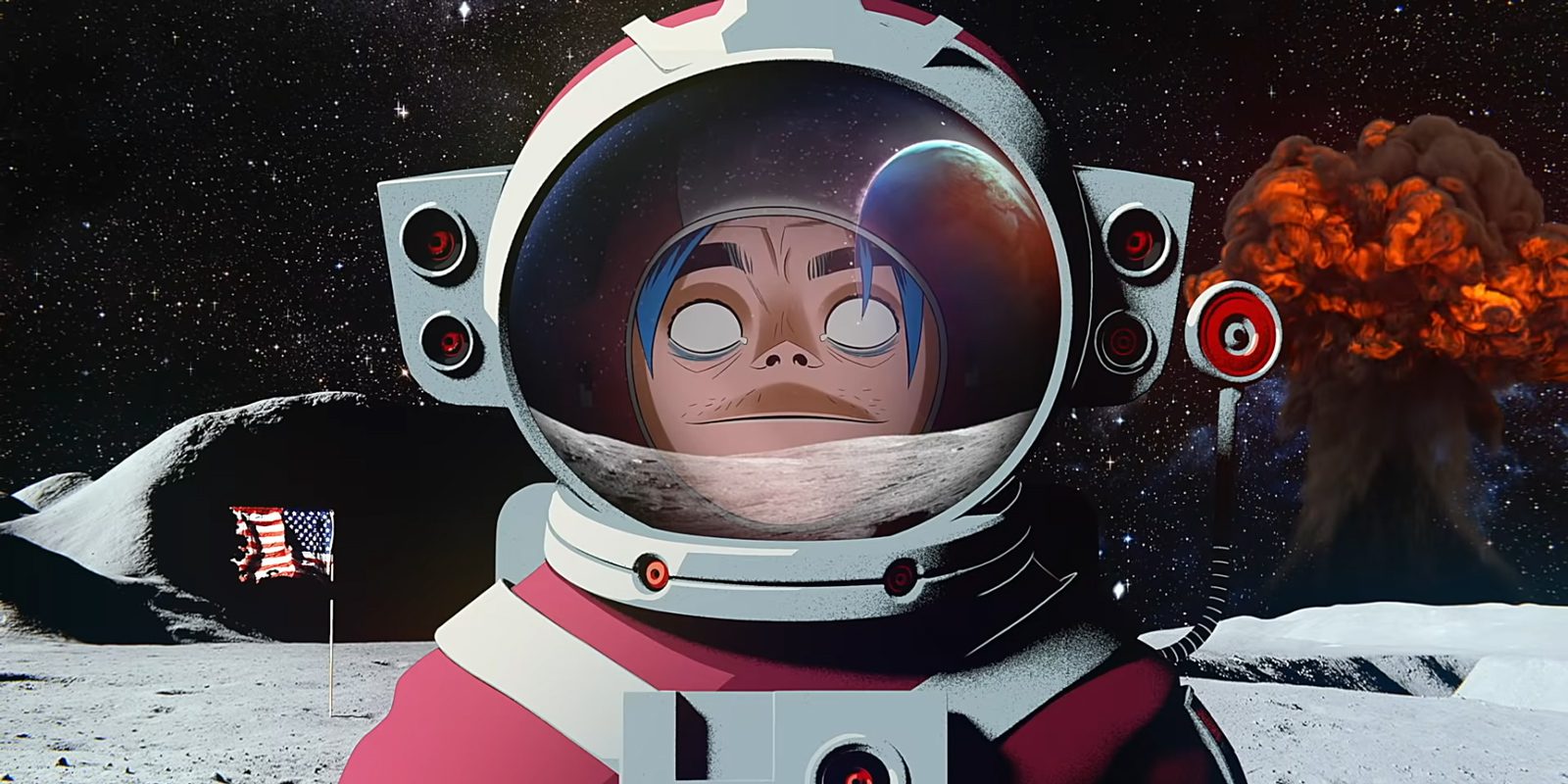

Over 500 museums uploaded their collections to Google

Art museums were hit by the pandemic in a strange way. They closed, then opened, then closed again with the second wave, many forced to shut down in the middle of exhibits that took months to build.

But they were some of the first institutions to respond to quarantine orders by giving away free content as an incentive for people to stay home, and they invested a lot of their newly-freed time into making sure their digitized paintings were better-organized and more available than ever before. This is in large part thanks to Google Arts & Culture, one of the tech giant’s unsung side projects that’s been doing some amazing cultural work behind the scenes.

Museums have been uploading photos of collection pieces to their own archives for years, but Arts & Culture has not only done an excellent job of compiling them—they’ve posted walkthroughs of the real buildings in Street View format.

The iconic Guggenheim museum can be viewed in its entirety, along with the D.C. National Art Gallery, Paris’s Musée d’Orsay, Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum and Van Gogh Museum, Los Angeles’s Getty Museum, Doha’s Museum of Islamic Art, Seoul’s Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, and over five hundred others.

Name-June Paik’s The More, The Better at the MMCA

The zoom resolution is incredibly high, almost, but not quite, enough to read the placards. But for that, there are annotations on the paintings you’re currently viewing in the bottom toolbar, some of which are more detailed than the ones you’d find in the museum. It’s as close as you can get to the gallery experience at home, with everything but the scale.

But wait!

There’s one way to get the scale, though: VR. Google Arts & Culture has a VR app available for Android and iPhone. It can be viewed through Google Cardboard or cast to Daydream View, and as you walk through the virtual museum, audio guides will be provided by actual curators.

Other museum tours have been uploaded to regular Street View, albeit without the supplementary information, and can be viewed in Google Earth VR. Arts & Culture has also been releasing 360 views of historical sites to their Youtube channel, like this one from February of Chauvet Cave’s famous paleolithic paintings.

The Smithsonian released 3 million images for free use

Albert Bierstadt’s “Among the Sierra Nevada, California,” from the American Art Museum

On February 25th, the Smithsonian announced the launch of Open Access, with the goal of releasing their entire collection into the public domain. They launched with 2.8 million images, which they emphasized was just the beginning, and are now at well over 3m. They not only allow the images to be used for photomanipulations and concept art, they encourage it with the slogan, “Create. Imagine. Discover.”

Paintings have been scanned in high-resolution, sculptures and artifacts have been placed on white backgrounds and photographed from sometimes tens of angles.

So,, I hear you ask, what are some of the things in it? 3,000-px-wide photos of every piece in the American Art Museum. High-resolution scans of Japanese scrolls and illustrations from the Bhagavata Purana. WWII propaganda posters. Turnarounds of rare violins. More scientific illustrations than you can count. 3d scans of dinosaur skeletons, the space shuttle Discovery, the Wright Brothers’ plane, Chinese vases, Charlie Parker’s saxophone, presidential statues, and women’s clothing from several eras.

The gallery can be found here.

(Thanks to allstrangenature on Tumblr and @SarahLovesHam on Twitter for passing this one on.)

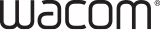

There was a renaissance in animated music videos

I can’t find an official confirmation of this, but 2020 seems to have blown away the record for the most released in one year. Consider July:

On the 10th, Dua Lipa debuted the Disney/Cuphead-inspired glam fantasy Hallucinate; the same day as late rapper Juice Wrld’s action-packed, anime-esque Come and Go, one of several this year for his posthumous last album. The 20th saw another one of Gorillaz’ trademark live-action/animation fusions, PAC-MAN, part of their ongoing video series “Song Machine.” The Weeknd tapped the black-owned anime studio D’ART Shtajio for a Boondocks-ian video for his hit single Snowchild, and dropped it on the 22nd. On the 24th, the Strokes put out the multimedia Ode to My Mind. On the 28th, Noah Cyrus and Sony released their collaboration for her single titled… well, July, animated (by the studio Media Molecule) with only the Playstation 4-based game maker Dreams and its controllers. And within two minutes of each other on the 30th, Billie Eilish posted her Studio-4C-esque My Future, and BENEE, whose animated avatar looks strikingly similar, her ghostly Night Garden.

(Because this one could use the exposure the most.)

That’s just one month, just in pop, and I’m sure I missed a few. Other months this year, especially in the summer hit season, have been similar. “This lockdown turned everyone into a cartoon character,” comments one Fábio Oliveira on My Future.

In fact, the video’s director, Andrew Onorato, expressed the same sentiment. “Every animator I know has been fully booked out all year,” he told Variety last month. Quarantine “has shown studios and agencies how viable animation is as an alternative to live-action.”

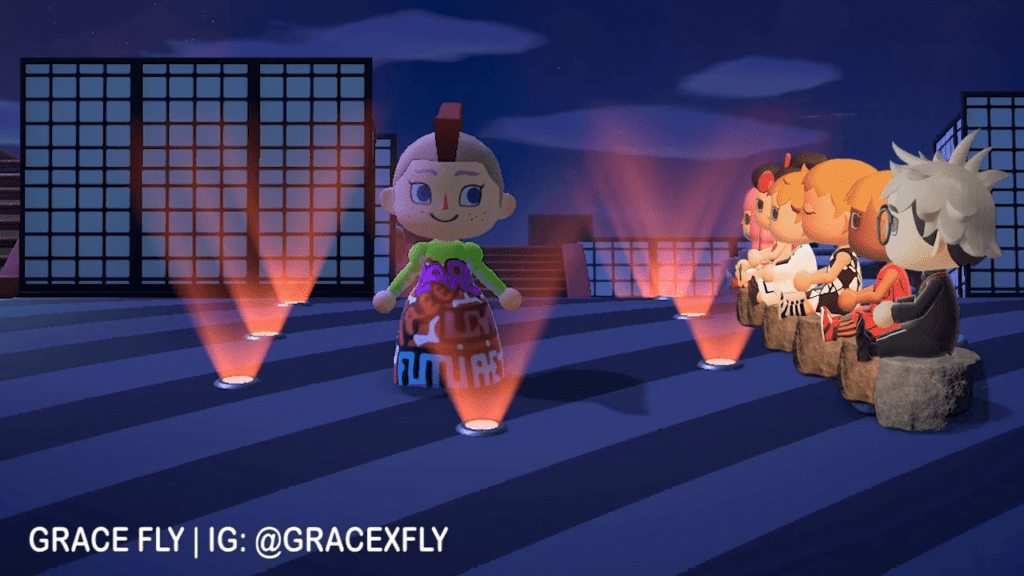

Animal Crossing spawned the cutest fashion scene ever

Out of the 7,838,346,104* people on Earth, I’m pretty sure I’m the only one who didn’t play New Horizons. All your favorite media personalities played it. All your friends played it. Your parents played it. Your kids played it, or will when you have them. Babies were born holding Nintendo Switches. It was the defining game of 2020, letting quarantiners escape into a world where the worst medical emergency is a wasp sting.

* As of 2:41 PM on January 11.

The series has come a long way since I played it on Gamecube in middle school, and watching footage of the newer ones, the most striking difference is the level of customization. You can alter the game’s default clothing, furniture, and architecture, all of which inspired amazing viral feats of worldbuilding.

Xqz-moi’s recreation of the High Line park

But none caused more hype than the clothing. In addition to being able to make clothing designs in-game, some apps and websites would let you turn JPGs and PNG’s into patterns for immediate export into the game, letting clothiers make their drip in image editing programs, or simply export their existing art. Designs could be shared via numerical ID’s or QR codes, letting them be passed around on social media along with images. Combined with the game’s popularity, this opened up a new channel of creative expression for artists.

And as with everything in 2020, it quickly became a Very Big Deal. Millions of patterns were created and shared, for everything from everyday casual wear to reproductions of iconic movie outfits. The subreddit for New Horizons clothing alone grew to 240,000 members—almost as many as r/LosAngeles, for comparison.

A commission market popped up, with artists being hired to create custom patterns in exchange for game currency or villagers. It adopted the practices of the real-life fashion industry, with players turning their houses into boutiques and popular designers becoming big names. “The Animal Crossing fashion community can be intense,” an anonymous one by the alias of Riley told Polygon. “There’s a lot of competition [to get] eyes on your stuff.”

Soon, people in the industry—many laid off just like other event workers—got into it. One popular example is the Instagram account Nook Street Market, where a designer, a model, and a photographer recreate real outfits from hot collections. Even some major companies, like Marc Jacobs and Valentino, released outfits.

From Nook Street Market

This peaked with in-game fashion shows by brick-and-mortar clothing companies. When designer and Manhattan boutique owner Carolina Sarria put hers on during Fall Fashion Week, she emphasized having the same staff that a real one would, with a hairstylist, a makeup artist, and avatars belonging to real supermodels. “I think it’s a really genius and innovative way of bringing the runway to life again,” said participant Aaron Philip, who in real life has headed up Sephora campaigns and starred in a music video alongside Miley Cyrus.

From the show

Designs for the digital outfits were sold for $5, which went to social justice charities, and can still be bought on Sarria’s site.

There was a promotional push for POC artists

A few years back, The Washington Post put it bluntly: “If you’re making a living as an artist, you’re probably white.” 2020, though, saw a collective effort to raise awareness of the racial disparities in art sales, hiring, and gallery presences, and with it, efforts to include POC, especially black people, in all parts of the arts.

There were exhibits and features for black artists, both traditional and digital. Databases were made of black creatives for hire. Magazines posted “Resources for hiring and celebrating black talent.” Industry professionals offered free portfolio reviews and career advice for POC on social media.

#drawingwhileblack, #blackartists, #blacklivesmatter, and #blackcreatives all trended over the summer. Museums across the country and in Britain hired black curators to help alleviate the establishment’s focus on Eurocentric classical art.

In hindsight, it might look like a brief halcyon period before it was back to business as usual. And sure, some of the efforts at inclusion were performative, and many were too fleeting to make a dent in overall hiring practices. But like all influential movements in the long term, some parts of it fell by the wayside, but others were absorbed into the culture at large, having an incalculable influence on future trends in the industry. And the effect that it had on the artists of color themselves is not to be overlooked either. Hopefully, it gave many black artists—as well as immigrant artists, native artists, and many more—the courage to apply for these jobs in the first place, without assuming they’ll be rejected for not being part of a monochrome in-crowd.

Side note: If you’d like more info on this, check out my article from the midst of it back in June.

The rise of English VTubers

Illustration for January’s “Hololive Festival” by Narumi-Nanami

Virtual YouTubers have been a sensation in Japan for four years now, but 2020 saw them go international.

For anyone not familiar with it, the whole phenomenon might look baffling from the outside, covered in abstruse memes and in-jokes. But it boils down to this: A 3d avatar is modeled, then rigged up for animation and exported to a facial-capture system that connects to your webcam, usually FaceRig or Adobe Animate. The character lives and matches your movements at the bottom of the screen, where the facecam usually goes in livestreams. Most VTubers are game streamers with personas, some wildly different from their real self.

Like any medium, anyone can get into it, but it can be crucial to get help with advertising and production. Enter Hololive, a Tokyo-based VTuber talent agency: They’re the Motown Records of anime avatars, dominating the scene with their roster of stars, and being picked by them is the streaming equivalent of having your band signed. And in April, they announced the launch of Hololive English.

Scattered English-language streamers had been doing their own thing the whole time, but having the VTube company legitimize and hire them really started the boom. It also proved it could be just as viable an income source as Twitch. The top 20 vTubers pulled in $15.6 million in chat donations alone, and an unquantifiable amount of ad revenue.

It also started an entire ecosystem of fan art and animations. For example, if you’ve ever had even a passing interest in VTubers, you’ve probably seen something by 2Snacks, a Brazillian animator who went viral for his amazingly detailed fan works. But it was a just three-second video that made him famous, made to audio of the Japanese VTuber Korone imitating a Banjo-Kazooie sound effect:

The video, and his later animations of her, were remixed and lip-synced to every famous song and movie quote imaginable. Top honors go to backtracks, who managed to edit the—once again, three-second—clip into this:

The following is just my opinion: While VTubers attract some of the same creepy Perfect-Blue stans as any other female internet personalities, they’re unabashedly a good thing. It adds another layer of art to the formula of a person sitting in front of a camera playing a game, and it has the massive benefit of letting its actresses stay anonymous and keep their personal lives safe.

VTubers are overwhelmingly twentysomething women, giving them an alternative to the lookism they might otherwise face when streaming. Twitch viewers often complain that—due half to the amount of competition and half to general internet toxicity—streaming for women sometimes degenerates into a beauty pageant where they’re judged for their makeup and cup sizes instead of anything they actually say or do on stream. Sexual comments can run rampant, and some have stories about being shamed for going online in casual clothes. Although there’s some irony, in that sense, in VTuber avatars being almost exclusively cute girls, they give the streamer a chance to succeed or fail based solely on their gaming, voice acting, and improv comedy skills. And yes, some stream art too.

If you’ve never watched VTubers and would like to try, the best English streamer to start with might be the calm and accessible Amelia Watson, or as a gateway to Japanese streamers, bilingual teakettle Pikamee. But my personal favorite is an indie, the wonderfully strange Yuni Luna. (Praise Lamp.)

You can commission your own rigged avatar from sites like Fiverr, generally starting around $100 for a quality one, and anime artist and modeler Terupancake told Polygon in September that orders had “gone up really quickly since the start of the year.”

—

Note: While I’ve been fortunate enough to be platformed by Wacom, opinions expressed here do not represent the company’s official stances on anything. Especially not who is best girl.

—

About the Author

CS Jones is a Philadelphia-based writer and illustrator whose 2020 involved publishing 35 articles for Wacom, working on two novels, buying a car, renting an apartment, and getting tear-gassed twice, but just because he happened to be in the neighborhood. His writing’s best seen at thecsjones.com, and his art at @thecsjones on Instagram.