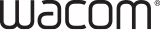

Character animation is a complex subject. If you’ve never tried it, it can feel like you’re trying to hit a moving target or rather, drawing a moving target. In this fun and informative tutorial, industry veterans Brent Noll and Maximus Paulson from BaM Animation break down four key motion principles and demonstrate them as they animate a dancing cat using Adobe Animate and ToonBoom Harmony on a Wacom Cintiq Pro.

Animation is overwhelming, and most artists think that since they can already draw, they could learn to animate pretty easily, and while it is true that being able to draw helps, it’s an entirely new skill set that takes time and practice.

Most people overestimate their abilities before they even draw the first frame, and that’s because they need to gain the understanding of movement principles. After all, animation does not equal illustration; animation equals movement.

According to The Animator’s Survival Kit by Richard Williams, there are 12 principles of animation. Still, we are going to focus on just four easy ones in this video to get you started.

I. Easing

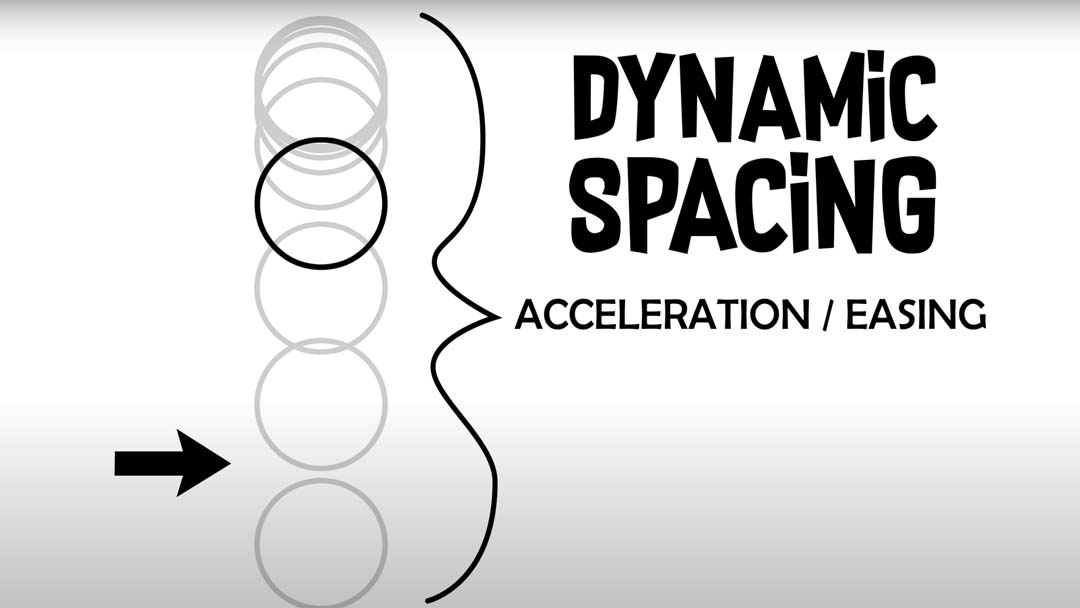

Easing is a fancy word for acceleration. Consider that a car cannot abruptly go from zero to sixty instantly; it’s highly unnatural. Cars are heavy and take time to speed up, and so do all objects or characters in motion. When an object takes time to speed up, we call this an ease out, and when it slows down to stop, we call this an ease in.

A movement that is eased correctly is more natural-looking: an object let go in mid-air eases out from its original height, but it does not ease in when it hits the ground. So knowing when to use eases is key as well. Instead, it maintains its original velocity and shoots back up, and then it can ease again at the top as it loses momentum.

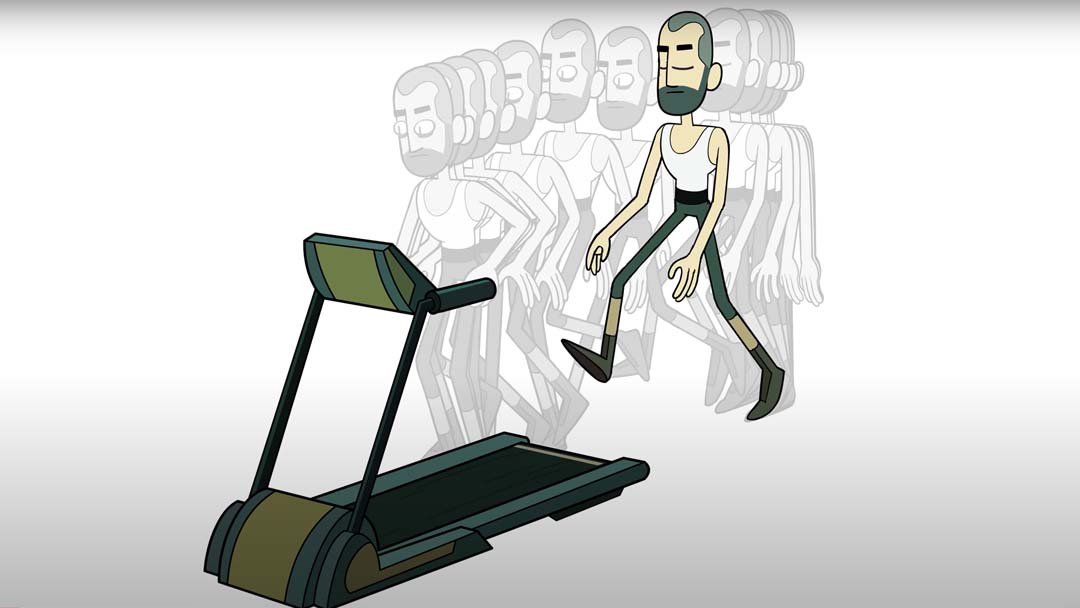

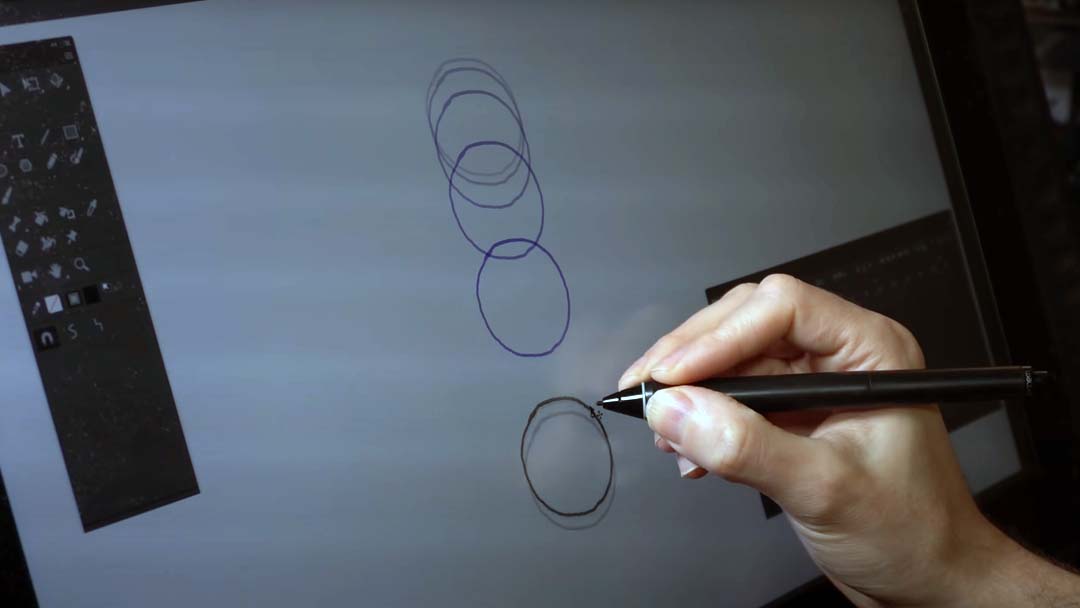

Because the animation’s frame rate is so constant, we achieve easing by adjusting the spacing between each drawing so that drawings close together make slow motion, and illustrations far apart make a fast motion. Notice how the drawings at the top are close together and then become further apart as the ball falls. This is called dynamic spacing, which is how you create acceleration or easing.

II. Overshooting

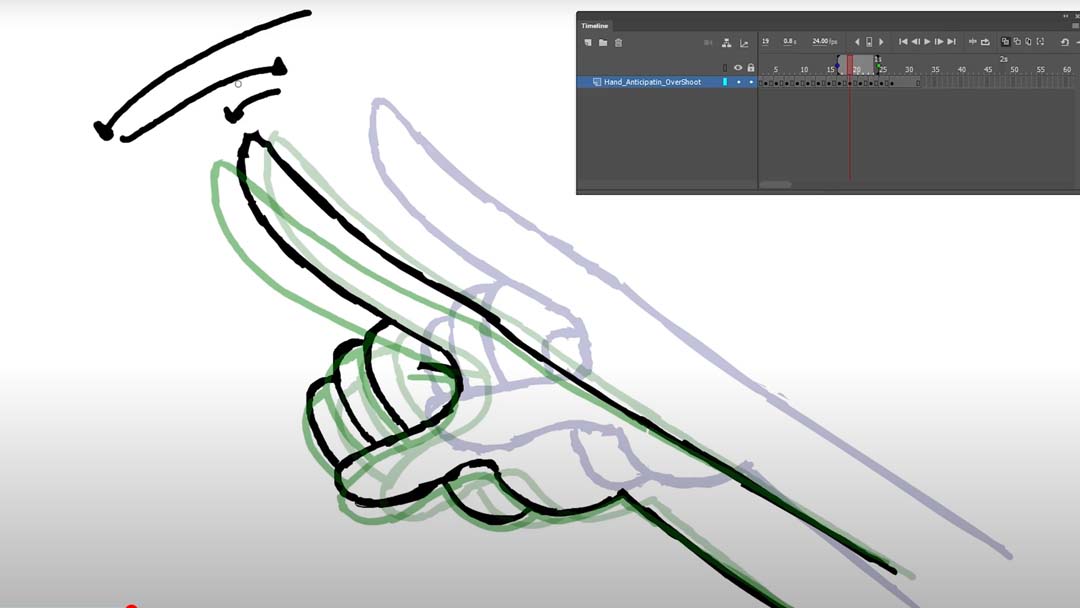

Let’s try animating a hand. Because we are learning to animate characters and move them from point A to point B, let’s add our second principle, overshooting, when an object goes past its final resting point only to snap back into place. This idea might seem overly cartoony, but it can add much life to your character’s movements.

In this example, I’m going to adjust the final frames to go past two frames; then it will move back here and then go a little bit forward, and then finally settle. Look at the difference! Now you can see how adding overshooting at the ends of your animation brings even more life. Of course, it’s not possible unless you’re a robot to come to a perfect stop, so unless you’re going for some crazy stiff warp, even just adding one frame of overshooting can do so much.

III. Squash and Stretch

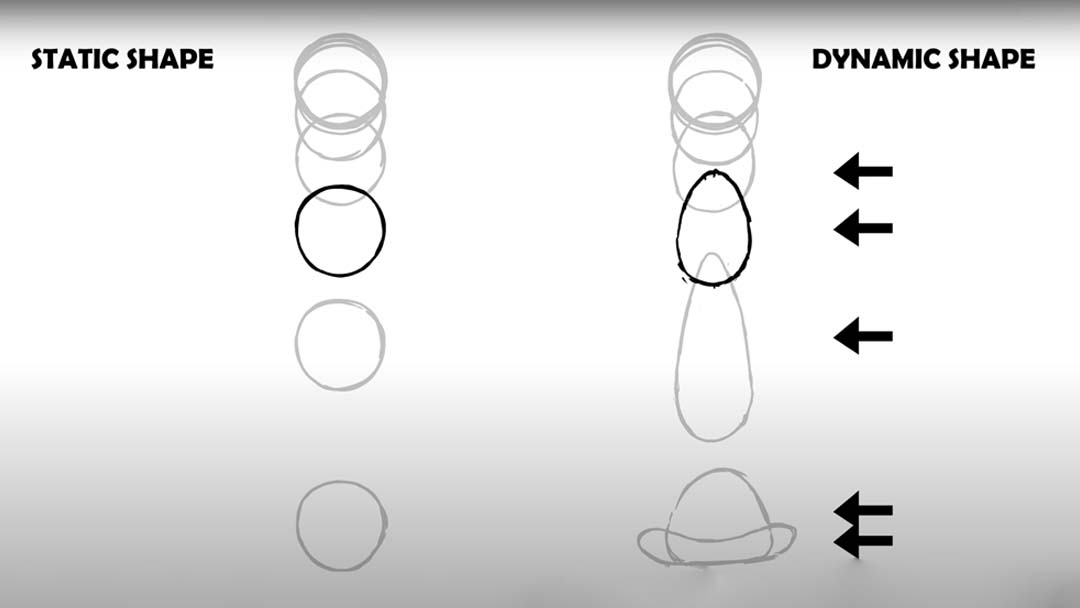

Characters are organic, and they change shape as they move. An animation should exaggerate that. Squash and stretch is a principle that emphasizes elasticity.

Please take a look at these two ball bounces: on the right, the ball is changing shape; it looks so much more malleable and elastic because I changed some frames to make them either look squished or stretched. This helps emphasize the movement. It may not seem like this is something you should do to characters, but squash and stretch can go a long way in conveying movement.

IV. Anticipation

In the hand example here, the hand just sort of moves forward, but what if there was a little hesitation – as if it was getting ready to move forward, like a wind-up for a pitch?

Let’s do something more subtle. Let’s first have the hand ease backward in these frames and then speed forward to its final position. Look at the difference! Anticipation is not always natural in every movement, but it is a lot nicer to look at and makes the acting more evident. As Alan Becker said, Anticipation “helps communicate actions to the audience by preparing them for the following action so they won’t miss it.”

The main difference between bad and good animation is that bad animation doesn’t move in interesting ways.

After seeing this demonstration of the four basic principles of animation, you may feel that you have a better grasp on distinguishing good motion from bad motion, but that doesn’t mean you’ll suddenly be able to animate like a 90s Disney animator. Instead, becoming a good animator requires a long series of training through learning exercises, starting from the very basics.

The most basic exercise many students start with is the ball bounce. It’s deceptively more complicated than it looks, though, and most people get it wrong because they open up their animation software, draw a ball, move it down slowly, and then back up and say, “Here! I’ve done it!” But done this way, the animation looks terrible; there’s no gradual spacing.

The better way to animate the ball bounce is to place the top frames close together and then gradually space them out to create dynamic acceleration. Then copy and reverse the frames.

But you can make it even more interesting by building on more techniques like squash and stretch and adding an impact frame. As your animation progresses, you’ll get strong enough to tackle more advanced assignments like a pendulum, a ball falling, a hand grabbing, a face turning, and in time, building up to a complete walk cycle. Learning to tackle simple movements will hone your eyes and prepare you for complex, multi-layered character movements.

About BaM Animation

BaM Animation was created by Burbank-based professional animation industry veterans Brent Noll and Maximus Pauson. They launched their popular YouTube channel in 2017 and found a unique and playful way to deliver informative and educational animation content in an engaging and memorable way.

Max draws the characters for BaM and is usually the live-action director and script supervisor. In his non-YouTube life, Max is an Emmy award-winning character designer who has worked on shows, including Rick and Morty, FutureWorm, Disenchantment, and Nico, and the Sword of Light.

Brent is in charge of backgrounds, animation, and many technical aspects of the show, including filming, audio, post-production, visual effects, and general troubleshooting. He also manages BAM’s social media presence. When he’s not working on BaM, Brent is a background and prop designer for shows including Rick and Morty, FutureWorm, Troll Hunters, and Final Space.

A popular feature of BaM is that they ask viewers to send their original art to the show so it can be featured in upcoming episodes. If you want to submit a piece for consideration, you can do so here.

For more from BaM Animation, check out BaM Animation on YouTube, their Website, their Discord, or their Instagram. Also check out Brent Noll or Maximus Pauson‘s websites, or Brent’s Twitch.